|

|

|

Vol.

22, No. 2

April 2017

Choosing Better Initial Foster Care Placements

Placement stability is a core goal of the child welfare system. Why? Because frequent moves have been tied to decreased child well-being, attachment difficulties, emotional trauma, low self-esteem, and behavior problems. Kids who move a lot in foster care are also more likely to run away or experience incarceration (Rubin, et al., 2007; Chamberlain et al., 2006; sources cited in Ahluwalia & Zemler, 2003).

Because moves can be traumatizing, North Carolina policy is that every child deserves one single, stable placement in a family setting within his or her own community (NC DSS, 2016). In other words, if we must place a child in out-of-home care we want to get it right the first time.

Too Many Moves

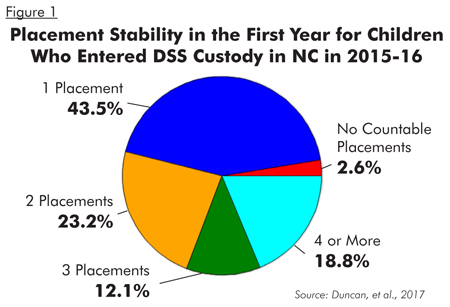

Apparently, it isn't easy. In 2015-16, 5,332 children entered DSS custody in our state. Upon entering care most of these children were placed either with relatives (37%), in family foster care (36%), or in a group home (8%). But as Figure 1 shows, for many of these children this initial placement did not last. Many moved two, three, or four or more times that year (Duncan, et al., 2017).

North Carolina's struggle in this area was reflected in its performance on the 2015 Child and Family Services Review (CFSR), where federal reviewers found stability of foster care placements (Permanency Outcome 1, Item 4) to be an area needing improvement (USDHHS, 2015).

Choosing the Best Possible Initial Placement

Placement instability is a problem with causes at the child, family, and system levels. While there is no simple fix, making better initial placements may help. Here are suggestions for reflecting on and improving your practice in this area:

Focus on the match. It is common sense that placements will be more stable if we choose them by matching the child's needs to resource parent strengths. This is backed up by research, which "shows a strong correlation between a child's behavior, the foster parents' ability to deal with that behavior, and placement stability" (Semanchin Jones, 2010). To make a good match it is essential to . . .

Use what you know about the child. One study (Ahluwalia & Zemler, 2003) found that agencies do not always use all the information they have about children when making placement decisions. For example, staff with the most knowledge of the child are not always very involved in placement decisions. If a placement move is needed, Ahluwalia and Zemler urge practitioners to talk with previous workers and caregivers to take advantage of what has been learned about the child.

Consistently assessing every child using a clinical or functional assessment (e.g., CAFAS, SDQ, CANS) may also be useful. This can help agencies understand children's needs and make informed leveling and other placement decisions (Chor, 2015; Doran & Berliner, 2001; Hartnett, et al., 2003).

Agencies should also take advantage of what we know about children who are most at risk for placement instability. While every child and placement is unique, research suggests moves are more likely for children who are older or who have behavioral problems, especially aggressive, destructive, or delinquent behaviors (Hartnett, et al., 2003). When placing children with these traits, clearly discuss concerns with prospective providers and build an adequate plan of support.

Get input from the child and family. Whenever possible, involve children in placement decisions. Children are more likely to understand moves and accept placements they help select (Ahluwalia & Zemler, 2003). This recommendation is in line with North Carolina policy, which requires use of child and family team meetings (CFTs) at many points, including at first placements and all subsequent moves. Even for emergency placements, agencies must call a CFT the next working day to review and evaluate the decision (NC DSS, 2016).

Know your providers. Knowing the strengths of the resource parents who will be caring for the child is the other key part of good matching. This calls for close communication between the licensing worker and the placing worker, if the agency supervises the foster family.

However, since more than half of children in DSS custody in North Carolina are cared for by private child-placing agencies, "knowing your provider" often requires a thorough exchange of information and a trusting relationship with a private agency. Know your private partners well, because agencies that are officially of the same level or type often offer very different kinds of services and structure (Doran & Berliner, 2001).

Provide full disclosure. Resource parents can make good judgments about whether they can meet a child's needs only if they know about those needs. For this reason, policy directs DSS agencies to tell resource parents as much as possible about the reason for the child's placement and the child's needs (NC DSS, 2015).

Conclusion

For more on placement decision making, see NC's child welfare policy: http://bit.ly/2mD6Bl5.