|

|

|

Vol.

23, No. 2

June 2018

Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT) for Opioid Use Disorder

In the field of child welfare today there is growing emphasis on evidence-based practice. While we have yet to develop a solid base of empirical evidence for much of what we do, there are interventions that have been proven to be indisputably effective and which we should embrace. Medication-assisted drug treatment (MAT), the gold standard for treatment of opioid use disorder, is one such intervention (Mittal, et al., 2017).

Opioids

Opioids include a variety of medications. They comprise both illegal drugs, like heroin, and pain medications that are available legally with a prescription, like fentanyl, oxycodone (OxyContin), hydrocodone (Vicodin), codeine, morphine, and others (NIDA, n.d.).

All opioids are chemically related. They work by binding with opioid receptors on nerve cells, which is how they reduce pain. Side effects of opioids include drowsiness, confusion, nausea, and constipation (SAMHSA, 2015). The drugs can also create euphoric feelings, or a "high," in some people, which can lead to misuse (NIDA, n.d.). When combined with certain genetic or psychological predispositions, opioid misuse can lead to addiction (Sheridan, 2017).

Opioid Use Disorder

Sometimes, even when people take opioids prescribed by doctors for medical conditions, they become dependent on the drugs. This dependence can lead to addiction, overdoses, and death (NIDA, n.d.).

Opioid use disorder (OUD) is a chronic brain disease related to ongoing use of opioids (Pew Charitable Trusts [PCT], 2016). Symptoms of OUD include a strong desire for opioids, inability to control or reduce use, continued use despite consequences, development of a tolerance, using larger amounts over time, and spending a lot of time to obtain and use opioids (SAMHSA, 2015). People with OUD can also experience severe withdrawal symptoms when they stop or reduce opioid use, such as negative mood, nausea or vomiting, muscle aches, diarrhea, fever, and insomnia (SAMHSA, 2015).

Addiction is complex and can be difficult to understand. People who are addicted may make choices that harm themselves or their loved ones. They may behave irrationally. This is because addiction causes parts of the brain to function improperly. Brain systems involving reward and pleasure, motivation, and memory malfunction in people who are addicted. They may pathologically pursue reward and/or relief by using substances. That intense drive can override other, healthier instincts (PCT, 2016).

MAT

Research shows people with OUD who abruptly stop using opioids and try to maintain abstinence on their own are likely to start using again. While relapses are often a normal part of the recovery process, they do increase the risk of fatal overdose (NIDA, 2018).

Medications are available that help people maintain abstinence from prescription pain pills or heroin by reducing or blocking the euphoric effects of opioids, relieving cravings, and reducing painful withdrawal symptoms (Kaplan, 2018).

Medications are most effective in treating addiction when combined with therapy and other types of social support. This combination of medication plus counseling is called medication-assisted treatment (MAT). MAT is the most effective treatment for opioid use disorders. It is more effective than therapy or medication alone (PCT, 2016).

MAT can be provided in inpatient settings, though many people receive it while participating in out-patient counseling (with groups or individually). Some people choose to supplement their MAT with participation in peer support groups (e.g., 12-step programs such as Narcotics Anonymous).

MAT Medications

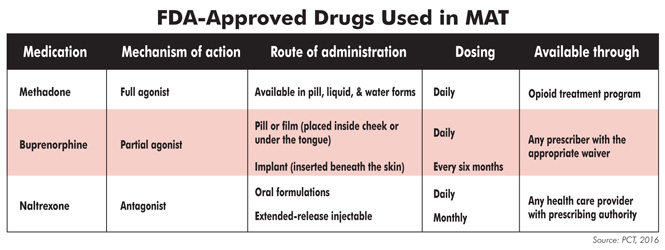

The three medications commonly used in MAT are methadone, buprenorphine (Suboxone, Subutex), and naltrexone (Vivitrol) (NIDA, 2016). Federal regulations require that methadone be administered in a certified opioid treatment program facility. Buprenorphine may be prescribed by an approved physician on a weekly or monthly basis. Naltrexone can be prescribed by any physician (PCT, 2016).

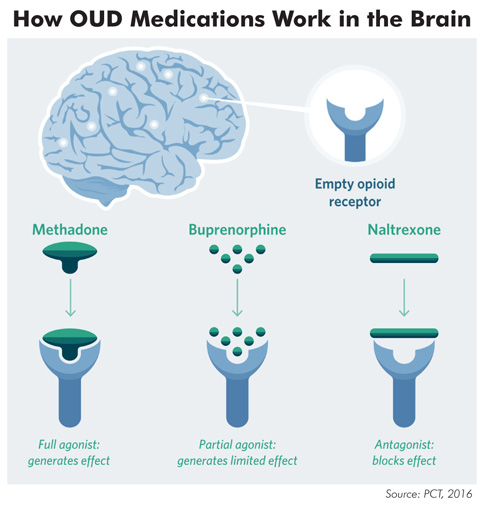

Each of these drugs works differently. Drugs that are agonists bind to the opioid receptors that heroin would bind to. Antagonists block these receptors, rather than binding with them, stopping opioid drugs from having any effect.

Methadone is a full agonist, meaning it lessens symptoms of opioid withdrawal and blocks the effects of other opioid drugs. Its effects last 24-36 hours. Even though methadone binds to and activates the brain's opioid receptors like heroin or other opioids would, methadone does not have the same euphoric effect because it binds much more slowly (NIDA, 2018). No optimal length of treatment for methadone has been established, but 12 months is usually considered the minimum amount (PCT, 2016).

Buprenorphine is a partial agonist, meaning it binds with opioid receptors, but not as strongly as a full agonist does. The medication's effects plateau after reaching a certain level, so people do not get a greater effect even with repeated dosing. Buprenorphine reduces cravings and withdrawal symptoms. It does not produce the euphoria of other opioids and has fewer dangerous side effects. Buprenorphine is available as a tablet, a film that dissolves in the mouth, or a subdermal implant that lasts 6 months. This can be a good option for people who struggle with taking a daily medication (NIDA, 2018).

Naltrexone is an antagonist. It prevents opioids from binding to opioid receptors. Naltrexone does not create a euphoric feeling, and therefore does not create dependence (PCT, 2016). If someone takes opioids while on Naltrexone, the opioids have no effect. Naltrexone can only be given to patients who have completely detoxed from opioids, so it is not an ideal option for early treatment (AATOD, 2017). One advantage of naltrexone is that it comes both as a daily pill and as a long-lasting injectable.

A physician should work with each individual to determine which medication would be best for their treatment plan based on their symptoms and needs.

Misconceptions and Misunderstandings

Misunderstandings about MAT have slowed the spread of this highly effective treatment. There is a misperception that MAT is just substituting one addiction for another, since some of the treatment medications are also opioids. Medications for OUD are prescribed to people who have developed a high tolerance for opioids. The dosage they receive helps prevent withdrawal and intense cravings, but does not create a euphoric effect or "high." Patients on MAT can function normally, drive safely, attend work or school, and be successful as parents (NIDA, 2018).

Patients may plan to wean off all medications eventually, but a decision about when that is safe to do must be decided between the patient and their doctor. The timeframe may depend on the severity of their addiction and any other health issues. Generally, medications used in MAT are tapered slowly over a period of months or years to give brain circuitry time to recover from prolonged drug use (NIDA, 2018).

Conclusion

Addiction is a chronic, life-threatening illness, like diabetes or hypertension. With those diseases, medications are often prescribed to control symptoms, in addition to the recommended lifestyle changes related to diet and exercise. Doctors familiar with MAT think of medications for opioid use disorders in the same way as they think of drugs for hypertension (Sheridan, 2017). These medications are a very important tool for fighting the opioid epidemic and for helping families torn apart by addiction.

Find MAT in NC |

|